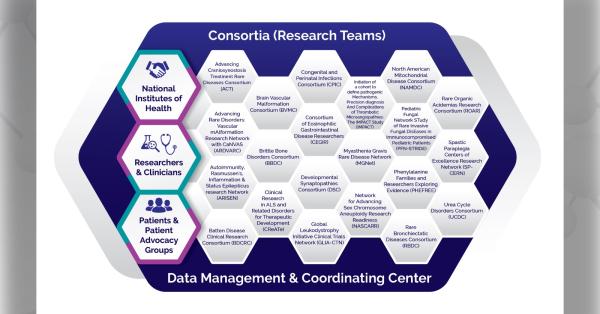

In patients with cavernous angioma (CA), lesions in the brain are caused by imbalances in the gut microbiome, according to a new study in the journal Nature Communications. Data from the Brain Vascular Malformation Consortium (BVMC) helped researchers make this connection, the first of its kind in any human neurovascular disease. BVMC is part of the National Institutes of Health’s Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network.

CA are blood vessel abnormalities that develop in the brain due to genetic mutations. The abnormally dilated blood vessels cause bleeding in the brain, strokes, seizures, and other serious neurological complications. Patients can experience a wide range of symptoms and outcomes.

How does the gut microbiome relate to CA? Although a previous study demonstrated that cells lining the blood vessels of the brain react to gut bacteria in mice, it was unknown if this would also apply to humans. To explore this possibility, a research team led by investigators at University of Chicago Medicine examined the gut bacteria of patients with CA.

Enrolling patients into this microbiome study involved collaboration between many key groups. Among them, researchers partnered with the BVMC team to access data and recruit patients from BVMC’s natural history study of patients with cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs).

Researchers then collected stool samples from more than 120 CA patients, analyzing for bacterial content and comparing with samples from the general population. They found that the CA samples showed significantly higher amounts of gram-negative bacteria, less gram-positive bacteria, and an abundance of three common bacterial species that can distinguish CA patients from those without CA lesions.

Overall, the network of bacteria in the CA samples was much more disordered when compared to the general population. This led to the discovery of the microbiome as a cause of lesions. Researchers showed that the bacterial imbalance in patients with CA produces lipopolysaccharide (LPS) molecules, which attach to blood vessel linings in the brain and cause lesions to develop.

By collecting blood from several CA patients, researchers were also able to identify the combination of molecular signals associated with the disease. Examining these blood biomarkers along with bacteria combinations allows researchers to measure the aggressiveness of CA in each patient.

The team aims to continue exploring this microbiome-brain connection. As they learn more about the gut microbiome, their findings could affect treatments for CA and other neurovascular diseases.

Read the full press release from University of Chicago Medical Center.